Change Point Regression

This implementation of change point regression was developed by Julian Stander (University of Plymouth) in Eichenseer et al. (2019).

Assume we want to investigate the relationship between two variables,

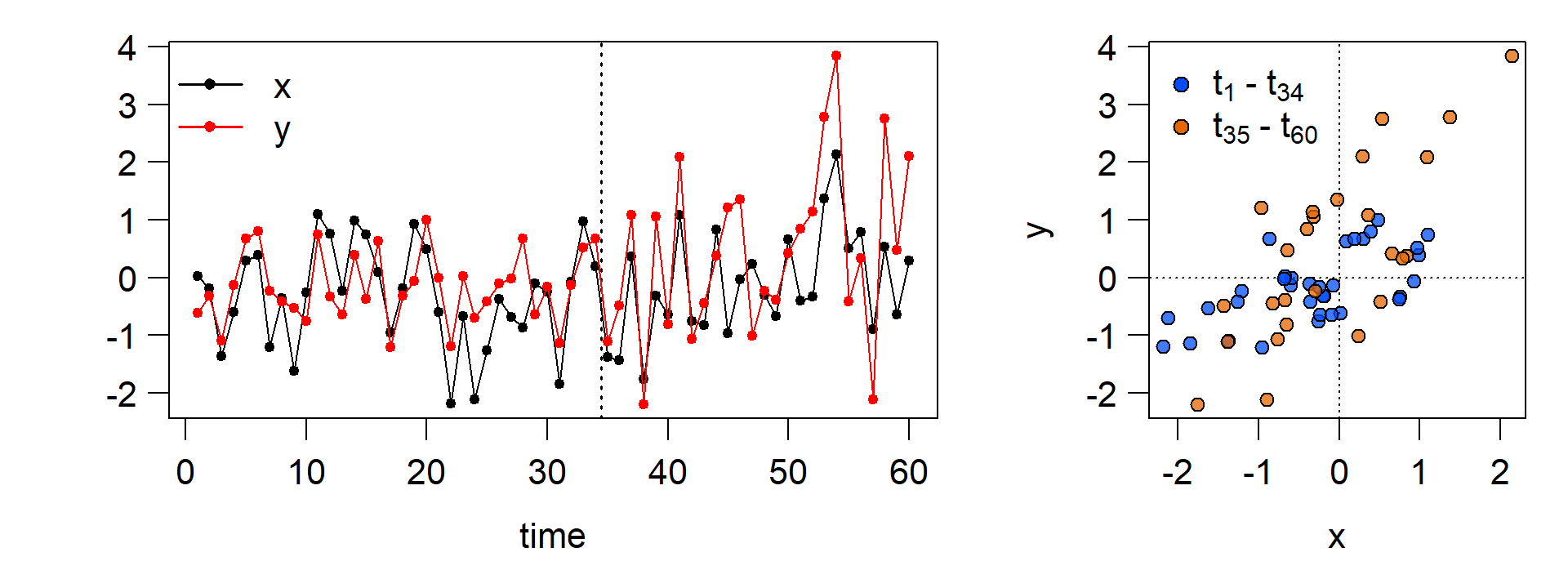

Let’s generate

set.seed(10) # change the seed for a different sequence of random numbers

n <- 60 # number of total data points

n_shift <- 35 # the data point at which we introduce a change

x <- rnorm(n,0,1) # generate x

y <- rnorm(n,0,0.5) + 0.5 * x # generate y without a change

y[n_shift:n] <- rnorm(length(n_shift:n),0,1) + 1 * x[n_shift:n] + 0.75 # introduce change

The regression model

Now we build a model that can recover the change point and the linear relationship between

The first part of this model looks like an ordinary least squares regression of

Here we have a single intercept (

From the change point

Implementation in JAGS

Here, we turn to the JAGS programming environment. Understanding a model written for JAGS is not easy at first. If you are keen on learning Bayesian modeling from scratch I can highly recommend Richard McElreath’s book Statistical Rethinking. We will access JAGS with the R2jags package, so we can keep using R even if we are writing a model for JAGS.

Bayesian methods for detecting change points are also available in Stan, as discussed here. An application using English league football data can be found here.

Below, we look at the model. The R code that will be passed to JAGS later is on the left. On the right is an explanation for each line of the model.

We save the model as a function named

model_CPR

Loop over all the data points

note that JAGS uses the precision

of

step takes the value

and

from

back-transform

again, the step function is used to define

We have to define priors for all parameters that are not specified by data.

because

Discrete prior on the change point.

model_CPR <- function(){

### Likelihood or data model part

for(i in 1:n){

y[i] ~ dnorm(mu[i], tau[i])

mu[i] <- alpha_1 +

alpha_2 * step(i - n_change) +

(beta_1 + beta_2 * step(i - n_change))*x[i]

tau[i] <- exp(log_tau[i])

log_tau[i] <- log_tau_1 + log_tau_2 *

step(i - n_change)

}

### Priors

alpha_1 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

alpha_2 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

beta_1 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

beta_2 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

log_tau_1 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

log_tau_2 ~ dnorm(0, 1.0E-4)

K ~ dcat(p)

n_change <- possible_change_points[K]

}Note that we put priors on

Prepare the data which we pass to JAGS along with the model:

# minimum number of the data points before and after the change

min_segment_length <- 5

# assign indices to the potential change points we allow

possible_change_points <- (1:n)[(min_segment_length+1):(n+1-min_segment_length)]

# number of possible change points

M <- length(possible_change_points)

# probabilities for the discrete uniform prior on the possible change points,

# i.e. all possible change points have the same prior probability

p <- rep(1 / M, length = M)

# save the data to a list for jags

data_CPR <- list("x", "y", "n", "possible_change_points", "p") Load the R2jags package to access JAGS in R:

library(R2jags) Now we execute the change point regression. We instruct JAGS to run three seperate chains so we can verify that the results are consistent. We allow 2000 iterations of the Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm for each chain, the first 1000 of which will automatically be discarded as burn-in.

CPR <- jags(data = data_CPR,

parameters.to.save = c("alpha_1", "alpha_2",

"beta_1","beta_2",

"log_tau_1","log_tau_2",

"n_change"),

n.iter = 2000,

n.chains = 3,

model.file = model_CPR)The results

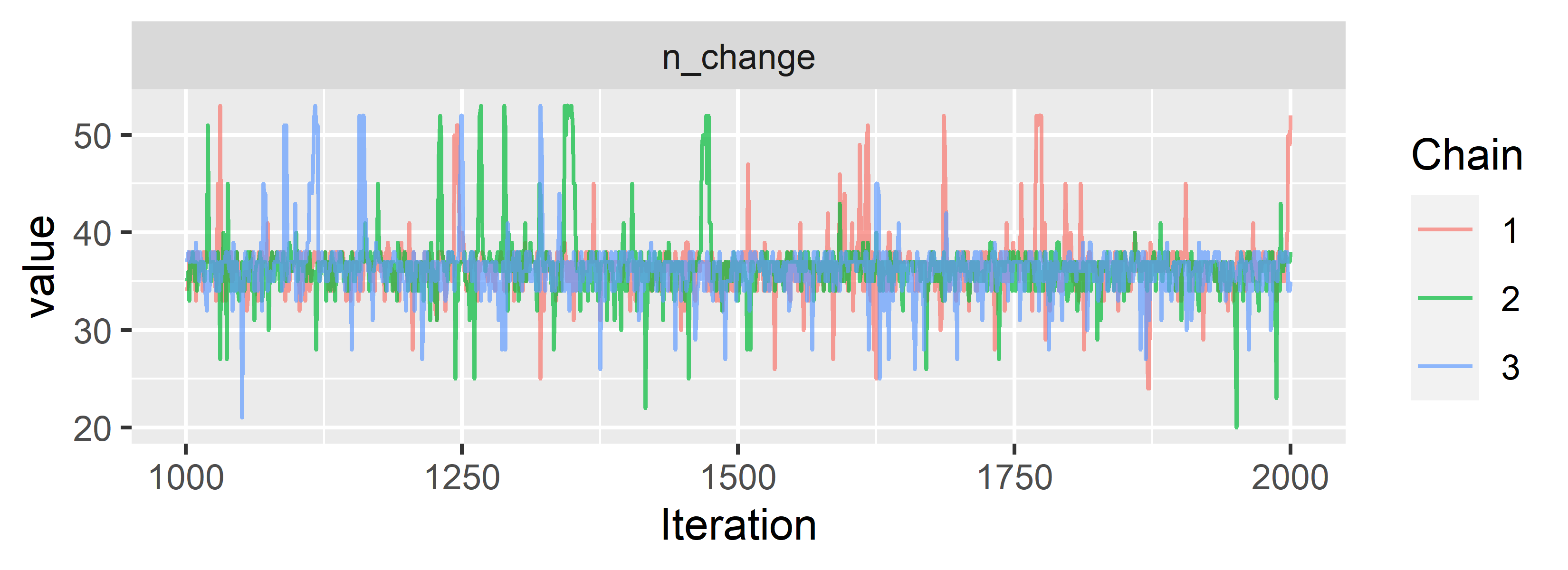

To visualise the results and inspect the posterior, we are using the ggmcmc package, which relies on the ggplot2 package. For brevity, we just look at the

library(ggmcmc)

CPR.ggs <- ggs(as.mcmc(CPR)) # convert to ggs object

ggs_traceplot(CPR.ggs, family = "n_change")

Looks like the chains converge and mix nicely. We can already see that our model locates the change point somewhere between

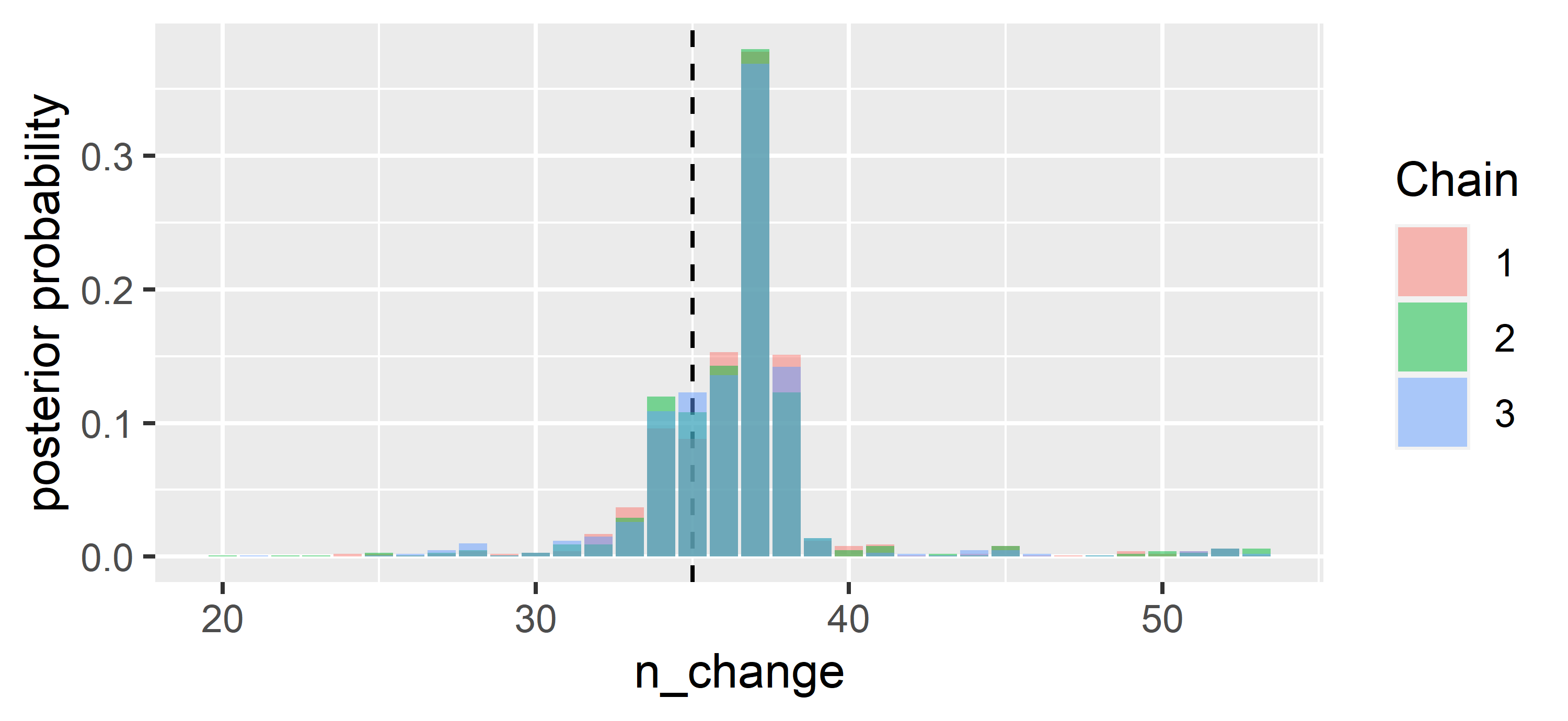

Let’s look at the posterior probabilities for the possible change points:

ggplot(data = CPR.ggs %>% filter(Parameter == "n_change"),

aes(x=value, y = 3*(..count..)/sum(..count..), fill = as.factor(Chain))) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 35,lty = 2) + geom_bar(position = "identity", alpha = 0.5) +

ylab("posterior probability") + xlab("n_change") + labs(fill='Chain')

The

Using the posterior distribution, we can answer questions like: “In which interval does the change point fall with 90 % probability?”

quantile(CPR$BUGSoutput$sims.list$n_change, probs = c(0.05, 0.95))## 5% 95%

## 33 39We can also inquire about the probability that the change point falls in the interval

round(length(which(CPR$BUGSoutput$sims.list$n_change %in% 34:38))/

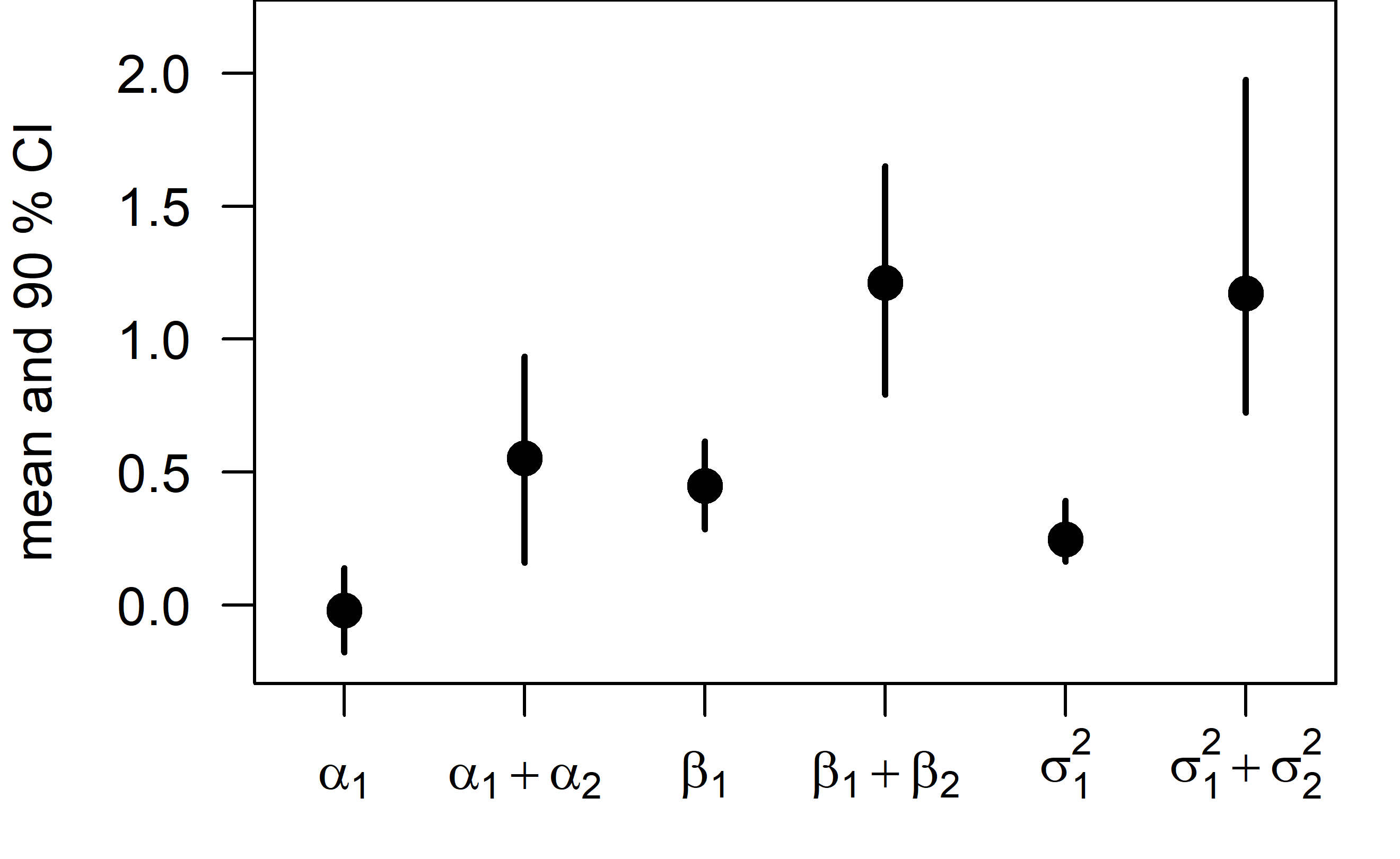

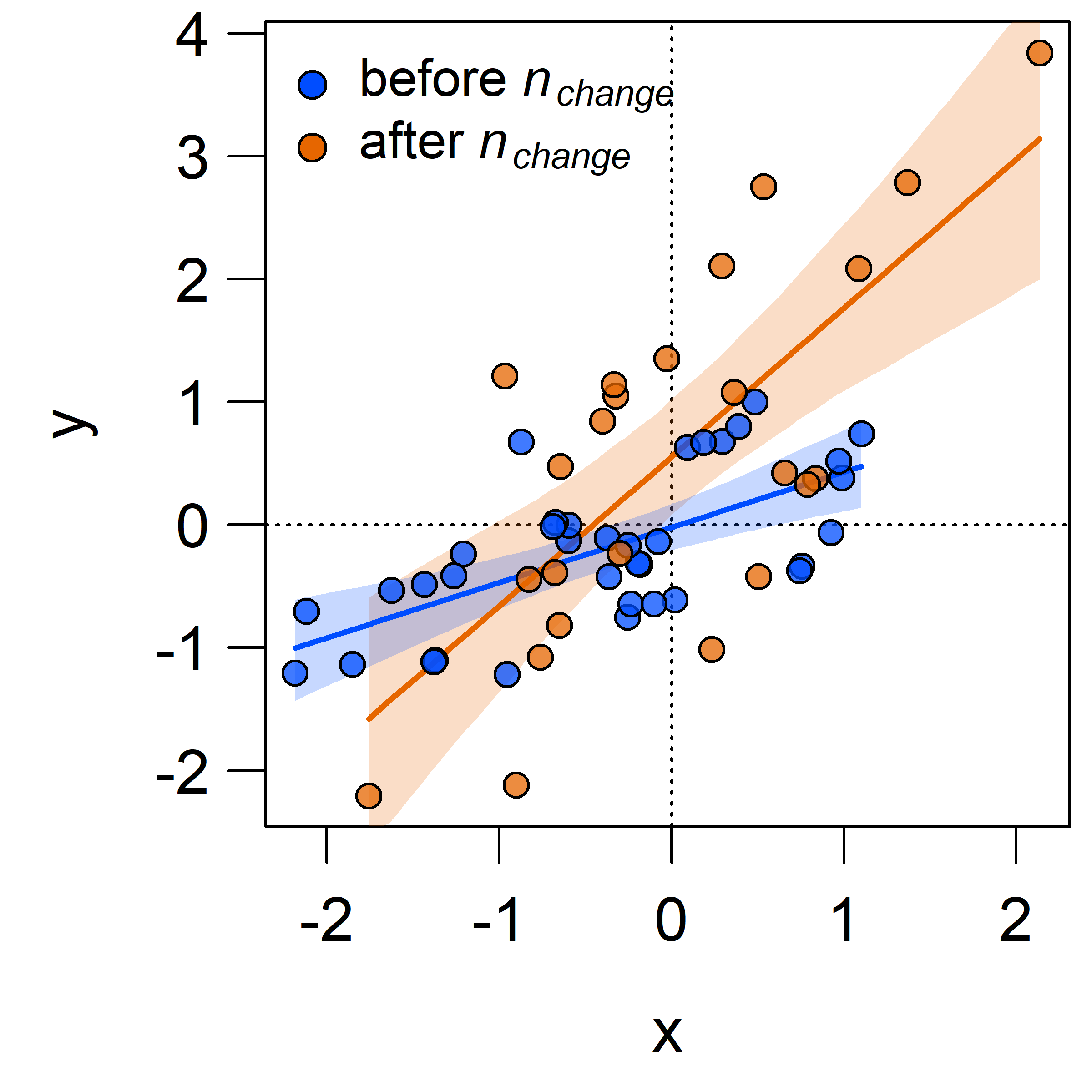

(CPR$BUGSoutput$n.sims),2)## [1] 0.87Finally, let’s have a look at the regression parameters and plot the resulting regressions before and after the most likely change point.

The intercept, slope, and residual variance all increase after the change point.

The intercept, slope, and residual variance all increase after the change point.

This can be immediately seen when plotting the change point regression:

The shaded areas denote

The shaded areas denote

You can find the full R code for this analysis at https://github.com/KEichenseer/Bayesian-Models/blob/main/01-Change_point_regression_with_JAGS.R

Get in touch if you have any comments or questions!