A Metropolis algorithm in R - Part 1: Implementation

The model presented herein uses modified code from https://khayatrayen.github.io/MCMC.html. I am currently developing a Metropolis-within-Gibbs algorithm for stratigraphic correlation of

13C records with Andrew R. Millard and Martin R. Smith at the Smith Lab at Durham University.

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are widely used to obtain posterior probabilities for the unknown parameters of Bayesian models. The Metropolis algorithm builds a Markov chain for each parameter, which resembles the posterior distribution. This works by selecting arbitrary starting values for the parameters and calculating the resulting joint posterior probability. Then, new values for the parameters are randomly proposed, and the joint posterior probability is calculated with the new parameter values. If the posterior obtained with the new values is higher than that of the current values, the new values will be recorded and added to the Markov chains. Otherwise, the new value will be accepted with a probability equal to the ratio of the two posterior probabilities. If the proposed values result in a much lower posterior probability than the current values, the proposal will most likely be rejected. This process is repeated many times, and the resulting Markov chains converge on the posterior distributions of the parameters. The Metropolis algorithm requires symmetric proposal distributions and is a special case of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm.

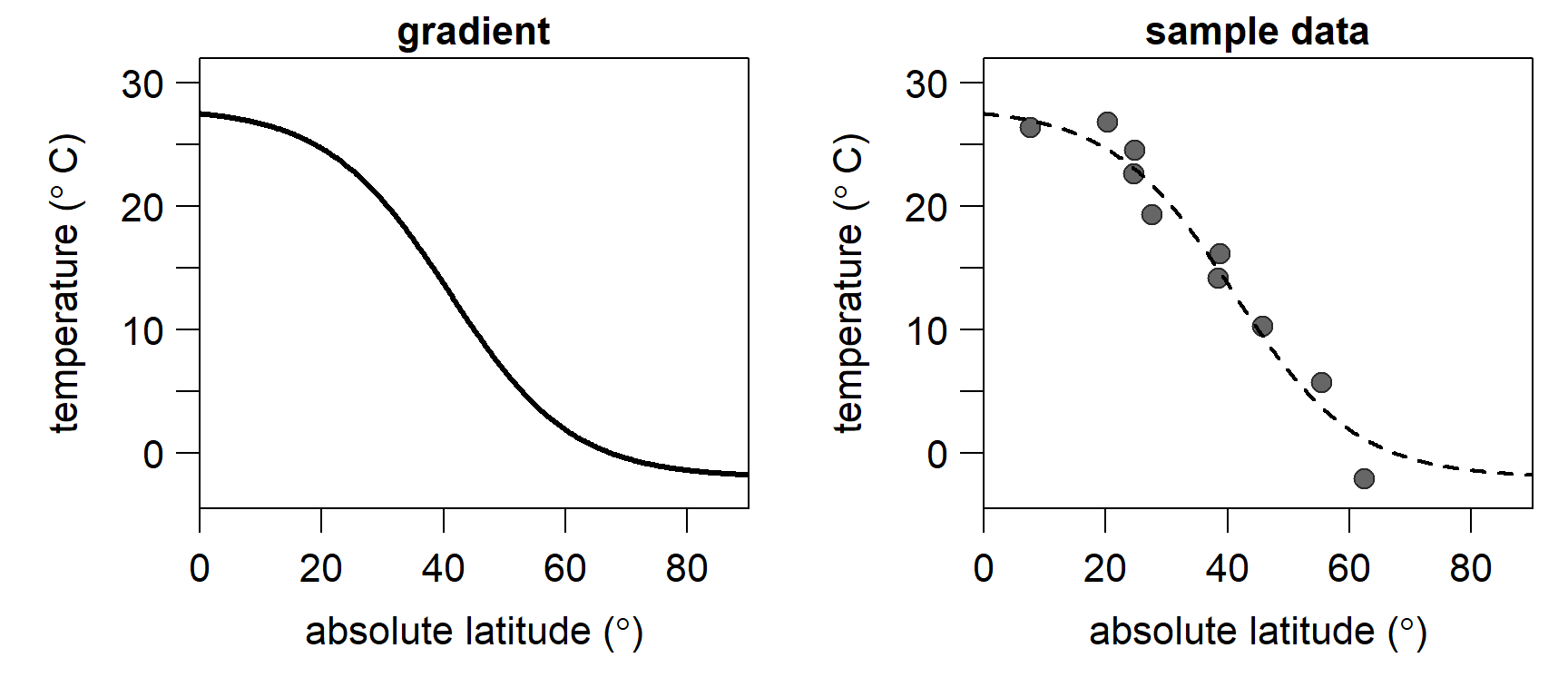

To illustrate the implementation of the Metropolis algorithm, we turn to climatology: Latitudinal temperature gradients from Earth history are difficult to reconstruct due to the sparse and geographically variable sampling of proxy data in most geological intervals. To reconstruct plausible temperature gradients from a fragmentary proxy record, classical solutions like LOESS or standard generalised additive models are not optimal, as earth scientists have additional information on past temperature gradients that those models do not incorporate. Instead, I propose the use of a generalised logistic function (a modified Richard’s curve) that can readily incorporate information in addition to the proxy data. For example, we can instruct the model to force temperature to continuously decrease from the tropics toward the poles.

To keep with the familiar notation in regression models, we set denote latitude as

In R code, we turn this into a function named

gradient <- function(x, coeff, sdy) { # sigma is labelled "sdy"

A = coeff[1]

K = coeff[2]

M = coeff[3]

Q = coeff[4]

return(A + max(c(K-A,0))/((1+(exp(Q*(x-M))))) + rnorm(length(x),0,sdy))

}As an example, let’s look at the modern, average latitudinal sea surface temperature gradient. We approximate it by setting

set.seed(10)

sample_lat <- runif(10,0,90)

sample_data <- data.frame(

x = sample_lat,

y = gradient(x = sample_lat, coeff = c(-2.0, 28, 41, 0.1), sd = 2))

Before writing the main Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) function, we pre-define a couple of supplementary functions that we use in every iteration of the Metropolis algorithm.

We start with the log-likelihood function, which translates to the joint probability of the data, given a specific set of model parameters:

loglik <- function(x, y, coeff, sdy) {

A = coeff[1]

K = coeff[2]

M = coeff[3]

Q = coeff[4]

pred = A + max(c(K-A,0))/((1+(exp(Q*(x-M)))))

return(sum(dnorm(y, mean = pred, sd = sdy, log = TRUE)))

}Next, we need a function to generate the log-priors, i.e. the joint prior probability of the set of model parameters. We specify the parameters of the prior distribution within the function for convenience. Uniform priors ranging from

logprior <- function(coeff) {

return(sum(c(

dunif(coeff[1], -4, 40, log = TRUE),

dunif(coeff[2], -4, 40, log = TRUE),

dnorm(coeff[3], 45, 10, log = TRUE),

dlnorm(coeff[4], -2, 1, log = TRUE))))

}The posterior is proportional to the likelihood

logposterior <- function(x, y, coeff, sdy){

return (loglik(x, y, coeff, sdy) + logprior(coeff))

}Finally, we define a function that proposes new values for the Metropolis-Hastings step. The magnitude of the proposal standard deviations (

MH_propose <- function(coeff, proposal_sd){

return(rnorm(4,mean = coeff, sd= c(.5,.5,.5,0.01)))

}With all the prerequisites in place, we can build the MCMC function. The model will update

run_MCMC <- function(x, y, coeff_inits, sdy_init, nIter){

### Initialisation

coefficients = array(dim = c(nIter,4)) # set up array to store coefficients

coefficients[1,] = coeff_inits # initialise coefficients

sdy = rep(NA_real_,nIter) # set up vector to store sdy

sdy[1] = sdy_init # intialise sdy

A_sdy = 3 # parameter for the prior on the inverse gamma distribution of sdy

B_sdy = 0.1 # parameter for the prior on the inverse gamma distribution of sdy

n <- length(y)

shape_sdy <- A_sdy+n/2 # shape parameter for the inverse gamma

### The MCMC loop

for (i in 2:nIter){

## 1. Gibbs step to estimate sdy

sdy[i] = sqrt(1/rgamma(

1,shape_sdy,B_sdy+0.5*sum((y-gradient(x,coefficients[i-1,],0))^2)))

## 2. Metropolis-Hastings step to estimate the regression coefficients

proposal = MH_propose(coefficients[i-1,]) # new proposed values

if(any(proposal[4] <= 0)) HR = 0 else # Q needs to be >0

# Hastings ratio of the proposal

HR = exp(logposterior(x = x, y = y, coeff = proposal, sdy = sdy[i]) -

logposterior(x = x, y = y, coeff = coefficients[i-1,], sdy = sdy[i]))

# accept proposal with probability = min(HR,1)

if (runif(1) < HR){

coefficients[i,] = proposal

# if proposal is rejected, keep the values from the previous iteration

}else{

coefficients[i,] = coefficients[i-1,]

}

} # end of the MCMC loop

### Function output

output = data.frame(A = coefficients[,1],

K = coefficients[,2],

M = coefficients[,3],

Q = coefficients[,4],

sdy = sdy)

return(output)

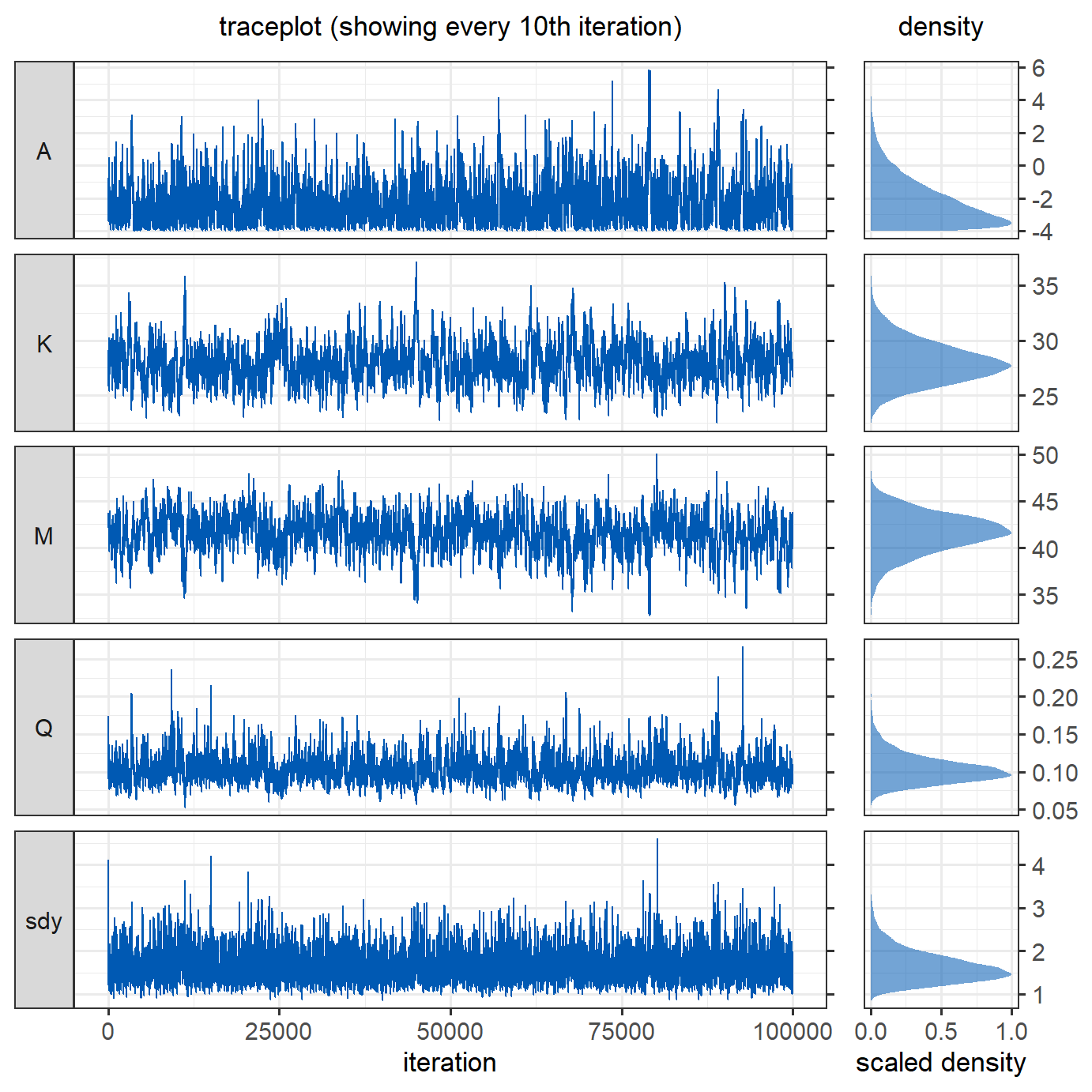

}To run the model, we need to provide starting values for the unknown parameters. We let it run for

nIter <- 100000

m <- run_MCMC(x = sample_data$x, y = sample_data$y,

coeff_inits = c(0,30,45,0.2), sdy_init = 4, nIter = nIter)To assess the model output, we produce trace plots and density plots of the posterior estimates of the parameters. For the trace plot, only every  The parameters have converged reasonably well.

The parameters have converged reasonably well.

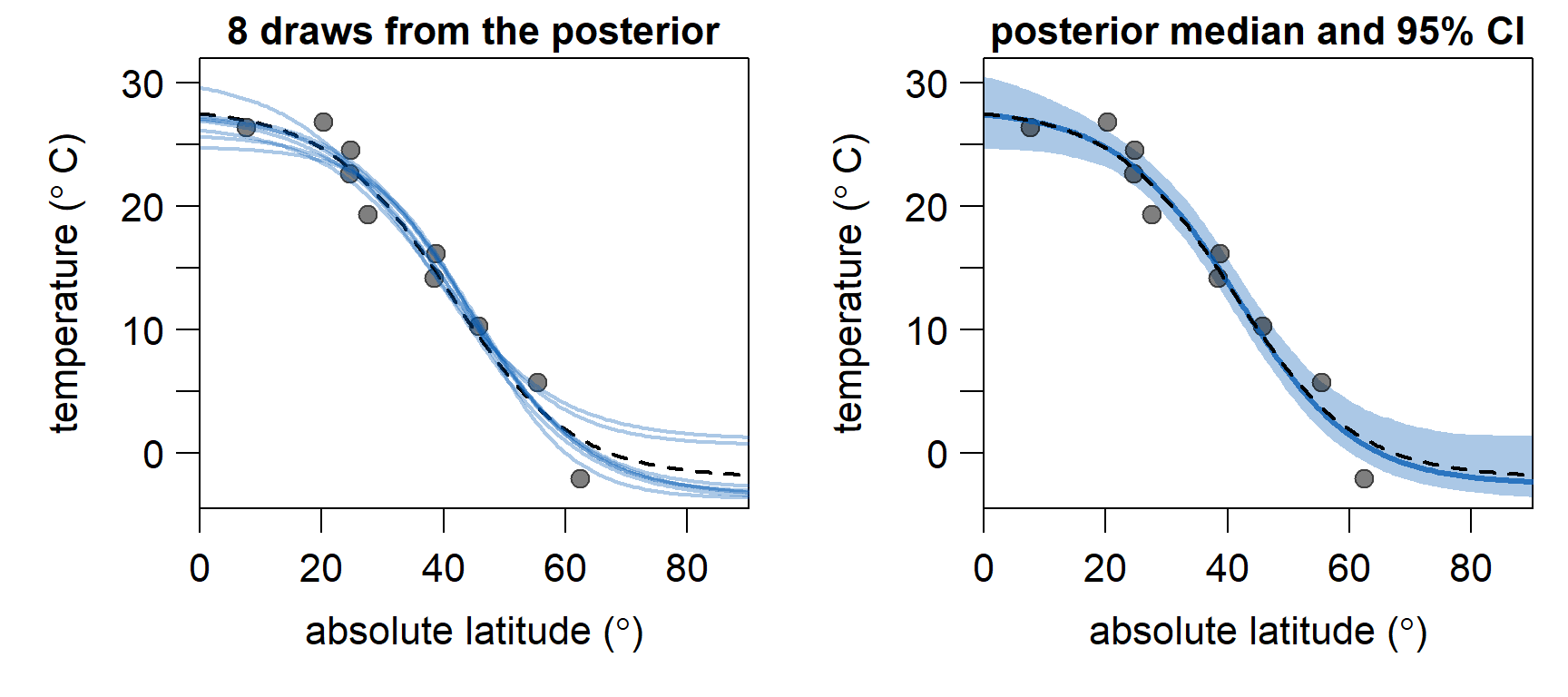

Below, we discard the first

In conclusion, the model seems to be doing a good job in estimating a sensible temperature gradient from sparse samples. In the second part of this series, we will implement adaption of

In conclusion, the model seems to be doing a good job in estimating a sensible temperature gradient from sparse samples. In the second part of this series, we will implement adaption of

You can find the full R code to reproduce all analyses and figures on Github.